Apple Patched iMessage. But Can It Be Made Safer Overall?

Application Security

,

Endpoint Security

,

Fraud Management & Cybercrime

Citizen Lab Says iMessage Exploit Delivered NSO’s Pegasus Spyware

Apple issued an emergency patch a software vulnerability on Monday that researchers say was used to deliver spyware via iMessage to the mobile phones of activists.

See Also: The Essential Guide to Container Monitoring

It’s an exploit-and-patch pattern that has repeated itself with vulnerable people often in the crosshairs. While software flaws can’t be completely eliminated from iMessage and iOS, a few changes to iMessage could make it safer overall for high-risk individuals, according to Patrick Wardle, an Apple security expert.

The vulnerability CVE-2021-30860, was used in an exploit that could infect devices with powerful spyware called Pegasus, made by the Israeli company NSO Group, according to researchers at Citizen Lab, a group within the University of Toronto. Citizen Lab reported the flaw to Apple less than a week ago and published its own findings on Monday.

UPDATE YOUR APPLE DEVICES NOW

We caught a zero-click, zero day iMessage exploit used by NSO Group’s #Pegasus spyware.

Target? Saudi activist.

We reported the #FORCEDENTRY exploit to @Apple, which just pushed an emergency update.

THREAD 1/https://t.co/dVuC1r1yUs pic.twitter.com/KHwtsWRcpA

— John Scott-Railton (@jsrailton) September 13, 2021

The flaw affects iOS before version 14.8, macOS versions before Big Sur 11.6m Catalina before Security Update 2021-005 and watchOS before 7.6.2. The patch fixes an integer overflow vulnerability in Apple’s image rendering library, which is called CoreGraphics.

The exploit is particularly potent because it requires no interaction from a victim who is targeted. These are sometimes referred to as “zero click” vulnerabilities and are among the most valuable and powerful ways to compromise a device.

Citizen Lab dubbed the exploit Forcedentry. Forcedentry is believed to have been used since at least February to deliver Pegasus. Citizen Lab says it found indications that Forcedentry had been used against a Saudi activist and activists in Bahrain after examining their devices. Forensic clues indicate that it was likely developed by the NSO Group.

Messaging applications such iMessage have large attack surfaces because the applications accommodate a huge range of file formats, which could result in buggy behaviors, says Wardle, who created the Objective-See suite of Mac security tools and formerly worked at the U.S. National Security Agency.

Using those vulnerabilities in iMessage to target people’s devices is “kind of just like shooting fish in the barrel,” Wardle says.

Free .GIFs? No Thanks

NSO Group has been repeatedly accused of selling its Pegasus spyware to governments.

Citizen Lab has documented that Pegasus has been turned on activists, dissidents or even, as in Mexico, used for targeting supporters of a tax on soda. Efforts to reach NSO Group were unsuccessful, but it has maintained that it vets the sale of the software and that abuse has been rare.

The clues that led to the latest vulnerability were files labeled as .GIFs, tweets John Scott-Railton, a senior researcher at The Citizen Lab. The files were intentionally mislabeled, however, and were actually Adobe PSD files, a format used with its Photoshop application, and PDF files. Sent via iMessage, those files in combination exploited the CoreGraphics library, which eventually resulted in the installation of Pegasus.

“[The victim’s] device becomes a spy in their pocket,” Scott-Railton tweets.

Citizen Lab and other researchers have documented in the past how vulnerabilities in Apple’s iMessage and other software has led to installation of NSO’s spyware.

In December 2020, Citizen Lab documented a zero-click vulnerability in iMessage called Kismet, which could hack Apple’s latest iPhone 11 running iOS 13.5.1.

In July, Amnesty International and a Paris-based journalist collective called Forbidden Stories released a report covering their investigation into the targeting of activists and journalists with Pegasus. The organizations concluded that iMessage was likely vulnerable to a zero-click exploit (see Spyware Exposé Highlights Suspected Apple Zero-Day Flaws).

Securing iMessage

For vulnerable people, there’s one option to nix exploits delivered through iMessage: turn it off and deregister an iMessage account. But that’s a terrible trade-off between usability and security since there’s no usability.

Switching to another messaging platform doesn’t necessarily increase safety, either. In 2019, NSO’s Pegasus spyware was forcibly installed on devices using CVE-2019-3568, a vulnerability in WhatsApp. And other messengers such as Signal share similar risks, as this remote code execution vulnerability in Signal’s desktop version in 2018 shows.

Even if security research can’t shake out all the vulnerabilities in iMessage or iOS, there are ways Apple could reduce the application’s attack surface, Wardle says.

Anyone can send anyone else an iMessage. That means knowledge of the victim’s phone number is enough to fire an exploit.

“[iMessage] is such a great distribution mechanism. [Apple] will route your exploit anywhere in the world to the target for you using end-to-end encryption. As an attacker, what more could you ask for?”

Wardle says that’s a much better scenario for an attacker than, say, email where a malicious message may be scanned by an ISP or security software. iMessage’s end-to-end encryption prevents visibility on malicious content. Often the only way to uncover exploits is what Citizen Lab has done by tediously following obscure forensic clues on victim’s phones.

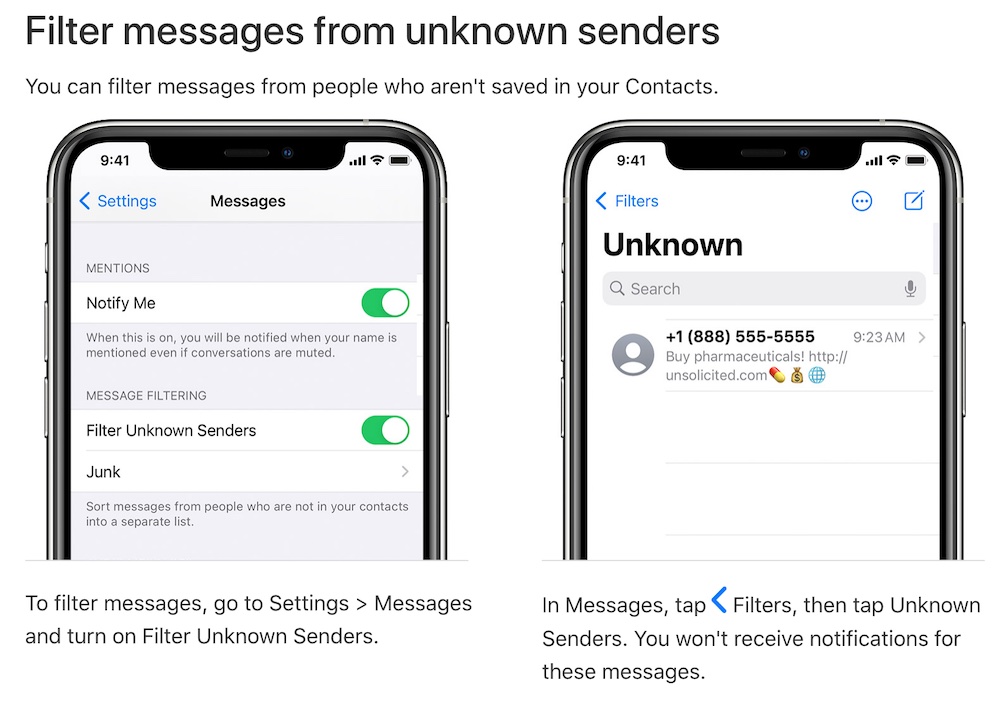

Apple does allow iMessage users to filter unsolicited iMessages from people not in someone’s contacts. But it appears those messages still reach the device, and it’s unclear if filtering those senders actually block attack code from executing. Turning that feature on, however, will put messages with potentially dangerous links in another bucket, perhaps making it less likely victims will click on a link.

Wardle says Apple could introduce a feature to turn off compatibility for all file formats and only allow text – no opening PDFs or dodgy Photoshop content, he says. Those kinds of security customizations have long been around for browsers, for example, like turning off JavaScript or, say, disabling Adobe’s bug riddled Flash Player.

“There’s a lot of third party plugins, plugins and extensions that really allow you to still use the browser, but really reduce the attack surface, which is great,” Wardle says. “That makes some very large percentage of exploits just not even applicable anymore.”

Messaging platforms are always adding new features to attract new users. But ironically, maybe adding the ability to shut off features would benefit users at high risk of surveillance the most.