Verkada’s Camera Debacle Traces to Publicly Exposed Server

Endpoint Security

,

Governance & Risk Management

,

Internet of Things Security

‘Arson Cat’ Hacker Tillie Kottmann Says She’s Not Worried About Law Enforcement

Tales of unsecure IoT cameras come along with regularity. But it’s going to be tough to top the system-wide failure revealed this week at California-based Verkada, the fast-growing cloud surveillance camera company.

See Also: The CISO’S Guide to Metrics that Matter in 2021

Verkada committed a relatively simple security failure, which arguably put many of its customers and members of the public at risk. As first reported by Bloomberg, a group of “somewhere in the middle of white and black hat” hackers gained access to more than 150,000 cameras deployed by large companies, schools, local government agencies and healthcare institutions (see: Startup Probes Hack of Internet-Connected Security Cameras).

“We just found it through going through … Shodan results as always.”

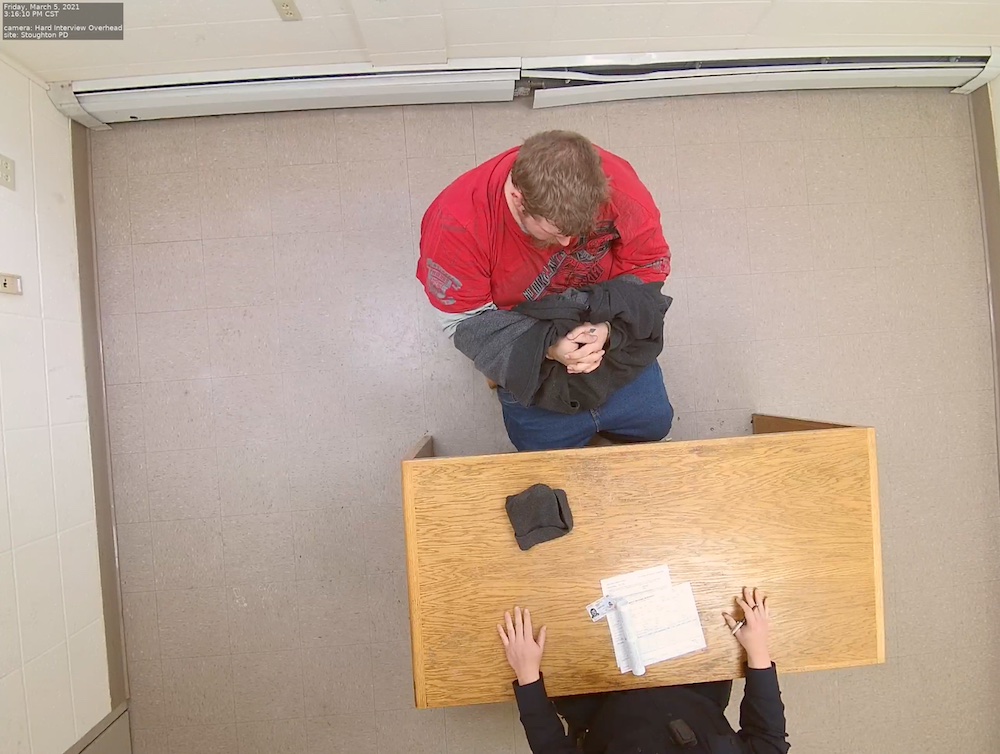

The feeds revealed private scenes: a family in its home completing a puzzle, convalescing patients in an intensive care unit, an apparent interrogation of someone handcuffed at the Stoughton Police Department in Massachusetts.

The hacker group, which goes by APT 69420, or the tongue-in-cheek codename Arson Cats, could view live feeds from the cameras, which were used in offices and factories by such high-profile technology firm as Tesla, Okta and Cloudflare.

The group said it was able to remotely gain root access to Verkada cameras, meaning the hackers could have manipulated the cameras in a variety of ways, including turning them off or installing custom firmware. Potentially, the access might also have served as a beachhead into a network, allowing more hackers to penetrate other systems.

Default Jenkins Configuration

I talked to Switzerland-based researcher Tillie Kottmann, a member of Arson Cats who also runs a Telegram channel called “Confidential and Proprietary.” The channel is a clearinghouse for leaked data, which Kottmann encourages her followers to submit for publication. The channel is prolific, and it’s hard to keep up with the volume of material.

While the Verkada security revelations might seem remarkable, Kottmann and the group zeroed in on the company and its 150,000 security cameras with ease.

“We just found it through going through … Shodan results as always,” Kottmann says, referring to the Shodan IoT search engine, which can be used to find specific kinds of devices or applications that are exposed to the internet (see: Shodan Founder: Using Search Engine to Find Vulnerabilities).

The results search turned up an internet-facing Jenkins server at Verkada, which the company says it used to manage numerous security cameras for a subset of its customers. Jenkins is a continuous integration platform used for software testing and development.

Kottmann has previously used Shodan to find internet-exposed Jenkins servers with exploitable flaws, for example, at Atlanta-based firm Maxex. Last October, I wrote about Maxex, which left open a Jenkins server that exposed complete mortgage documentation for at least 23 people in New Jersey and Pennsylvania (see: Home Loan Trading Platform Exposes Mortgage Documentation).

Kottmann says both Maxex and Verkada left their Jenkins servers publicly accessible via the internet, and that any unauthenticated person could have had unfettered access to everything on the exposed servers via a “super administrator” account. Ironically, in the case of Verkada, access to that account was protected by two-step verification, but the fact that the server had been left open for public access obviated that defense.

Kottmann says the credentials for the super admin account were hardcoded into Jenkins. Kottmann tells me a Python script regularly inserted the needed time-based one-time password.

Kottmann says Jenkins “has this handy, groovy shell feature which is basically RCE [remote code execution] but as a feature. You can browse the build workspaces.” A root shell opens in a web browser for any security camera that’s selected from a list, she says.

Bloomberg subsequently reported that as many as 100 Verkada employees had super admin access. Verkada said it has policies that ensure customers are aware of access to video feeds by its employees.

The super admin account has a convenient feature that allowed Kottmann and her crew to hit one button and download data about Verkada cameras plus their users in a standard .csv file. The data included users’ email addresses, names and organizations. The file Arson Cats obtained lists more than 157,000 cameras.

In a statement issued Thursday, Verkada CEO Filip Kaliszan says his company has called in FireEye’s Mandiant digital forensic unit as well as the law firm Perkins Coie to investigate.

One question is whether anyone else had already found the Jenkins server via a Shodan search and accessed the cameras. The TLS certificate for the Jenkins server was created in February 2019, although that doesn’t necessarily mean the server went live then.

how long were @VerkadaHQ‘s CI server and hardcoded backdoor credentials exposed publicly on the internet? since 2019-02-26? https://t.co/mXz8s4GtcUhttps://t.co/4o0OEJHn9J

— crash override (@donk_enby) March 10, 2021

Kottmann says based on “what we saw and what it seemed like, I don’t think someone used this access before us. But there is obviously no way to tell right now, and I don’t want to speculate.”

Opening a Door to the Wider Network

IoT cameras may be connected to the same network as other enterprise resources, which means if an attacker gains access to a vulnerable camera, they might be able to use it to pivot into the wider enterprise network.

Security experts say one best practice is to restrict surveillance cameras to a separate network. Cloudflare, for example, says this is exactly how it had configured its Verkada cameras, which it used in some offices.

As a result, Cloudflare dismissed suggestions by the hacker group that its infrastructure faced any danger of further exploitation, noting that it uses a “zero trust” model – referring to a methodology that uses fine-grained controls to ensure that anything that is connected to the network has little if any wider access, unless explicitly granted.

But beyond big companies with well-heeled security budgets and a well-trained security team, a malicious attacker might also have targeted the networks of hospitals, school districts, local governments and other types of organizations that use Verkada cameras, and which may not have segregated their network access.

“I doubt most of these customers properly do network separation,” Kottmann tells me. “And even if not used to pivot into corporate networks, having root shells on 150,000 [cameras] could have also allowed anyone to simply turn them into a botnet.”

Kottmann says she doesn’t notify organizations prior to publishing or leaking material tied to a breach, but Verkada arguably caught a lucky break. After Kottmann contacted Bloomberg offering it the scoop, Bloomberg notified the company before publishing.

Verkada cut the group’s access off around noon PST on March 9 prior to Kottmann going public, so there was no additional risk of this leak prompting a rush to access the cameras. Not long after she started tweeting information about the leaks, Twitter suspended her account, which it has done before with other accounts she created.

Legal Consequences?

Whether Kottmann and the group will face legal consequences from the exercise remains to be seen. Verkada says it has contacted the FBI.

Asked if she’s worried about the feds, Kottmann says: “Not really.”

A half a day after I spoke to Kottman, Bloomberg reports that her apartment was raided on Friday. The warrant, however, “was based on an alleged hack that took place last year and not on the recent breach of Verkada,” Bloomberg writes.

Of course, what Kottmann and her group did in regards to Verkada is a crime and a violation of privacy rights. But Verkada should be thankful an intruder didn’t do far worse than outline an egregious security lapse.