NATO Summit: Live Updates – The New York Times

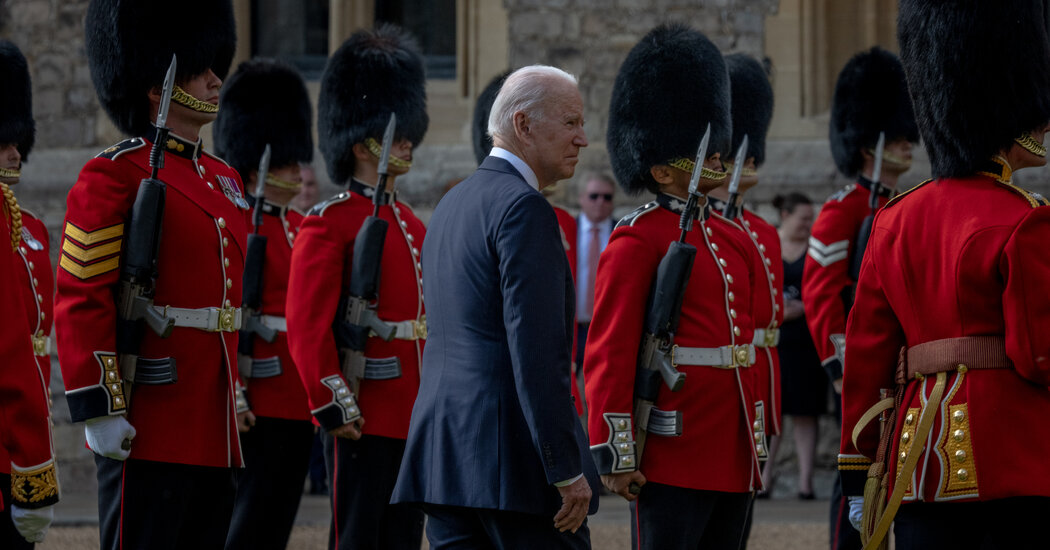

BRUSSELS — New United States presidents traditionally get an early, brief NATO summit meeting, as President Biden is on Monday in a session lasting less than three hours.

Few involved with NATO can forget the last time a new American president paid an inaugural visit. It was May 2017, and Donald J. Trump took the opportunity to deride the new $1.2 billion headquarters building as too expensive, and refused, despite the assurances of his aides, to support NATO’s central tenet of collective defense, the famous Article 5 of the founding treaty.

Mr. Biden, by contrast, is a longstanding fan of NATO and of the trans-Atlantic alliance it defends, so simply showing up with a smile and warm compliments for allies will go a long way to making his first NATO summit as president smooth and even unmemorable.

He drove that point home upon arriving at the summit on Monday morning in a brief greeting with Jens Stoltenberg, NATO’s secretary general — saying that the alliance was “critically important for U.S. interests” and pointing to Article 5 as a “sacred obligation.”

“There is a growing recognition over the last couple years that we have new challenges,” Mr. Biden said. “We have Russia, which is acting in a way that is not consistent with what we had hoped, and we have China.”

NATO also wants to show that it is not nearing “brain death,” as President Emmanuel Macron of France once complained, but instead preparing to adapt for a very different future.

The traditional communiqué is traditionally long — it is now 79 paragraphs — and was finished early Saturday evening.

How the 30 member nations agreed to describe the challenge of a more aggressive Russia and a rising China will be of particular interest and will set a tone for the alliance. China is considered more a challenge than a threat, but the wording on Russia is tough.

The leaders will also sign off on a decision to spend next year updating NATO’s 2010 strategic concept, which 11 years ago saw Russia as a potential partner and never mentioned China. New challenges from cyberwarfare, artificial intelligence, disinformation, and new missile and warhead technologies must be considered to preserve deterrence, and Article 5 will be “clarified” to include threats to satellites in space and coordinated cyberattacks.

There will be other issues for the leaders to discuss, even in a short meeting that is to provide each leader only five minutes to speak.

NATO is leaving Afghanistan pretty abruptly, after Mr. Biden’s decision to pull all United States troops out by Sept. 11. Many of NATO’s troops have already left. One of the main questions that remain: Can NATO continue to train Afghan special forces outside Afghanistan, and where?

Leaders will also talk about how to better prepare NATO’s “resilience,” including how to reduce dependence on Chinese-made technology, protect satellites and measure increased military spending. They want a new relationship with technology companies and new NATO partnerships in Asia.

They will begin to discuss a replacement for the secretary general, Mr. Stoltenberg, who worked hard to keep Mr. Trump from blowing up the alliance, and whose term ends in September 2022.

But for Mr. Biden, the meeting will be a bath of good feeling — and that is thought to be enough for now.

The NATO summit communiqué, a document of 45 pages and 79 complicated paragraphs that leaders will approve on Monday, deals explicitly with China’s military ambitions for the first time, according to a copy obtained by The New York Times.

But while Russia is described as a “threat” to NATO, China is described as presenting “challenges.”

Both President Biden and President Donald J. Trump before him put more emphasis on the threats that China poses to the international order, partly in terms of its authoritarian system and partly in terms of its military ambitions and spending.

NATO’s secretary general, Jens Stoltenberg, has said that China’s military budget is second in the world only to that of the United States, and that China is rapidly building its military forces, including its navy, with advanced technologies.

In a discussion of “multifaceted threats” and “systemic competition from assertive and authoritarian powers” early in the document, NATO says that “Russia’s aggressive actions constitute a threat to Euro-Atlantic security.” China is not called a threat, but NATO states that “China’s growing influence and international policies can present challenges that we need to address together as an alliance.”

NATO promises to “engage China with a view to defending the security interests of the alliance.’’ Separately, NATO officials have said that China is increasingly using Arctic routes, has exercised its military with Russia, sent ships into the Mediterranean Sea and has been active in Africa. China is also working on space-based weaponry as well as artificial intelligence and sophisticated hacking of Western institutions.

Much lower in the document, China comes up again, and is again described as presenting “systemic challenges,” this time to the “rules-based international order.” NATO also cites China’s expanding nuclear arsenal and more sophisticated delivery systems as well as its expanding navy and its military cooperation with Russia.

In a gesture toward diplomacy and engagement, the alliance vows to maintain “a constructive dialogue with China where possible,” including on the issue of climate change, and calls for China to become more transparent about its military and especially its “nuclear capabilities and doctrine.”

Some NATO states worry that President Biden appears to be rewarding President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia by meeting him on Wednesday in Geneva.

Skeptics say that the new United States president, his sights set squarely on the challenges posed by the rise of China, may be “sleepwalking” into an unwise rapprochement with a power that many European leaders view as their principal threat.

NATO leaders, who are gathering at a summit meeting on Monday, have usually gone out of their way to adjust to the strategic priorities of the group’s most powerful member, the United States. But the issue of China is more problematic, because NATO is a regional military alliance of Europe and North America. Its main concern remains a newly aggressive Russia — not distant China.

China is expanding militarily, exercising with Russia, sending its ships into the Mediterranean. It also has a base in Africa. So it has gotten NATO’s attention.

But NATO member states from Central and Eastern Europe, as well as Germany, are concerned that a new concentration on China will divert alliance attention and resources from the problem closer to home.

Russia has invaded Ukraine and stationed thousands of troops on its borders. It has poisoned and imprisoned dissidents at home, and abroad has hacked Western governments and companies and propped up President Aleksandr G. Lukashenko’s even more oppressive Belarus.

Russia has also developed sophisticated new intermediate-range missiles that can carry nuclear warheads and modernized its armed forces significantly, making Europe more vulnerable.

“Even though European opinion is becoming more hawkish toward China, European countries are concerned with getting onboard with an overly confrontational U.S. approach,’’ said Michal Baranowski, the director of the Warsaw office of the German Marshall Fund.

There is new concern, he said, after Mr. Biden decided to waive sanctions on companies involved in finishing the controversial natural-gas pipeline between Russia and Germany called Nord Stream 2.

In Poland, Mr. Baranowski said, “there is increased worry and the perception that Washington is going soft on Putin and sleepwalking into a reset with Russia.” Poland, he said, is not alone in saying: Let’s not overdo it with China.

Monday’s NATO summit meeting of 30 leaders is short, with one 2.5-hour session after an opening ceremony, leaving just five minutes for each leader to speak.

The main issues will be topical — how to manage Afghanistan during and after the withdrawal of United States troops, Vladimir V. Putin’s Russia, Xi Jinping’s China and Aleksandr G. Lukashenko’s Belarus.

The leaders will also sign off on an important yearlong study on how to remodel NATO’s strategic concept — the group’s statement of values and objectives — to meet new challenges like cyberwarfare, artificial intelligence, antimissile defense, disinformation and “emerging disruptive technologies.”

In 2010, when the strategic concept was last revised, NATO assumed that Russia could be a partner. China was barely mentioned. The new one will begin with very different assumptions.

NATO officials and ambassadors say there is much to discuss down the road: questions like how much and where a regional trans-Atlantic alliance should try to counter China, what capabilities NATO needs and how many of them should come from common funding or remain the responsibility of member countries.

How to adapt to the European Union’s still vague desire for “strategic autonomy,” while encouraging European military spending and efficiency and avoiding duplication with NATO, are other concerns. So is the question of how to make NATO a more politically savvy institution, as President Emmanuel Macron of France has demanded, perhaps by establishing new meetings of key officials of member states, like national security advisers and political directors.

More quietly, leaders will talk about replacing the current NATO secretary general, Jens Stoltenberg, whose term was extended for two years to keep matters calm during the Trump presidency. His term ends in September 2022.

For the last four years, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey has crushed opponents at home and cozied up to Moscow, while showering his allies with sweetheart government contracts and deploying troops regionally wherever he saw fit.

And for the most part, the Trump administration turned a blind eye.

But as Mr. Erdogan arrives in Brussels for a critical NATO meeting on Monday, he faces a decidedly more skeptical Biden administration. President Biden and Mr. Erdogan will have a brief meeting on Monday afternoon during the summit.

Whereas President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia has responded to the new order by growing even more belligerent, things aren’t that simple for Mr. Erdogan. Thanks to both the pandemic and his mismanagement of the economy, he faces severe domestic strains, with soaring inflation and unemployment, and a dangerously weakened lira that could set off a debt crisis.

So Mr. Erdogan has dialed back his approach, softening his positions on several issues in the hope of receiving badly needed investment from the West. He has called off gas exploration in the eastern Mediterranean, an activity that infuriated NATO allies, and annoyed Moscow by supporting Ukraine against Russia’s threats and selling Turkish-made drones to Poland.

Yet Mr. Erdogan does have some important cards to play. Turkey’s presence in NATO, its role as a way station for millions of refugees, and its military presence in Afghanistan have given him real leverage with the West.

As President Biden and his NATO counterparts focus on nuclear-armed Russia at their summit meeting on Monday, they may also face a different sort of challenge: growing support, or at least openness, within their own constituencies for the global treaty that bans nuclear weapons.

The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, the Geneva-based group that was awarded the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize for its work to achieve the treaty, said in a report released on Thursday that it had seen increased backing for the accord among voters and lawmakers in NATO’s 30 countries, as reflected in public opinion polls, parliamentary resolutions, political party declarations and statements from past leaders.

The treaty, negotiated at the United Nations in 2017, took effect early this year, three months after the 50th ratification. It has the force of international law even though the treaty is not binding for countries that decline to join.

The accord outlaws the use, testing, development, production, possession and transfer of nuclear weapons and stationing them in a different country. It also outlines procedures for destroying stockpiles and enforcing its provisions.

The negotiations were boycotted by the United States and the world’s eight other nuclear-armed states — Britain, China, France, India, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan and Russia — which have all said they will not join the treaty, describing it as misguided and naïve. And no NATO member has joined the treaty.

Nonetheless, an American-led effort begun under the Trump administration to dissuade other countries from joining has not reversed the treaty’s increased acceptance.

“The growing tide of political support for the new U.N. treaty in many NATO states, and the mounting public pressure for action, suggests that it is only a matter of time before one or more of these states take steps toward joining,” said Tim Wright, the treaty coordinator of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons who was an author of the report.

Timed a few days before the NATO meeting in Brussels, the report enumerated what it described as important signals of support or sympathy for the treaty among members in the past few years.

In Belgium, the government formed a committee to explore how the treaty could “give new impetus” to disarmament. In France, a parliamentary committee asked the government to “mitigate its criticism” of the treaty. In Italy, Parliament asked the government “to explore the possibility” of signing the treaty. And in Spain, the government made a political pledge to sign the treaty at some point.

There is nothing to prevent a NATO country from signing the treaty. And the bloc’s solidarity in opposing the accord appears to have weakened, emboldening disarmament advocates.

NATO officials have been outspoken in their opposition to the treaty. Jessica Cox, director of nuclear policy at NATO, said “nuclear deterrence is necessary and its principles still work,” in an explanation of NATO’s position posted on its website less than two months ago.

“A world where Russia, China, North Korea and others have nuclear weapons, but NATO does not, is not a safer world,” she said.

After President Biden meets his Russian counterpart on Wednesday, the two men will not face the news media at a joint news conference, United States officials say.

Instead, Mr. Biden will face reporters by himself after two private sessions with President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia, a move designed to deny the Russian leader an international platform like the one he received during a 2018 summit in Helsinki, Finland, with President Donald J. Trump.

“We expect this meeting to be candid and straightforward, and a solo press conference is the appropriate format to clearly communicate with the free press the topics that were raised in the meeting,” a U.S. official said in a statement sent to reporters this weekend, “both in terms of areas where we may agree and in areas where we have significant concerns.”

Top aides to Mr. Biden said that during negotiations over the meetings, to be held at an 18th-century Swiss villa on the shores of Lake Geneva, the Russian government was eager to have Mr. Putin join Mr. Biden in a news conference. But Biden administration officials said that they were mindful of how Mr. Putin seemed to get the better of Mr. Trump in Helsinki.

At that news conference, Mr. Trump publicly accepted Mr. Putin’s assurances that his government did not interfere with the 2016 election, taking the Russian president’s word rather than the assessments of his own intelligence officials.

The spectacle in 2018 drew sharp condemnations from across the political spectrum for providing an opportunity for Mr. Putin to spread falsehoods. Senator John McCain at the time called it “one of the most disgraceful performances by an American president in memory.”

Mr. Putin has had a long and contentious relationship with United States presidents, who have sought to maintain relations with Russia even as the two nations clashed over nuclear weapons, aggression toward Ukraine and, more recently, cyberattacks and hacking.

President Barack Obama met several times with Mr. Putin, including at a joint appearance during the 2013 Group of 8 summit in Northern Ireland. Mr. Obama came under criticism at the time from rights groups for giving Mr. Putin a platform and for not challenging the Russian president more directly on human rights.

In the summer of 2001 — before the Sept. 11 terror attacks — President George W. Bush held a joint news conference with Mr. Putin at a summit in Slovenia. At the news conference, Mr. Bush famously said: “I looked the man in the eye. I found him to be very straightforward and trustworthy. We had a very good dialogue. I was able to get a sense of his soul.”

At the time, then-Senator Biden said: “I don’t trust Mr. Putin; hopefully the president was being stylistic rather than substantive.”

Biden administration officials said on Saturday that the two countries were continuing to finalize the format for the meeting on Wednesday with Mr. Putin. They said that the current plan called for a working session involving top aides in addition to the two leaders, and a smaller session.