Yearlong Phishing Campaign Targets Energy Firms

Business Email Compromise (BEC)

,

Cybercrime

,

Fraud Management & Cybercrime

Oil and Gas Industry Yet Again a Victim of Agent Tesla Malware

A campaign that uses remote access Trojans and malware-as-a-service infrastructure for cyber espionage purposes has been targeting large international energy companies for at least a year, according to cybersecurity company Intezer.

See Also: Live Panel | Zero Trusts Given- Harnessing the Value of the Strategy

The campaign uses spear-phishing emails to steal browser data and private information – including banking details – as well as to log keyboard strokes, using malicious code such as Formbook and Agent Tesla, along with Loki, Snake Keylogger and AZORult, the Israeli company’s report says (see: Attackers Target Oil and Gas Industry With AgentTesla).

In addition to energy companies, the campaign also attacks the IT, manufacturing and media sectors. Its targets are primarily based in South Korea but include companies in the U.S., the United Arab Emirates and Germany as well, Intezer says.

The attack also targets oil and gas suppliers and is often only the first stage in a bigger campaign, the report says. “In the event of a successful breach, the attacker could use the compromised email account of the recipient to send spear-phishing emails to companies that work with the supplier. Thus using the established reputation of the supplier to go after more targeted entities.”

While Intezer did not offer details on the number of companies affected by the attacks, it notes that 68% of the victims are in the oil, gas and energy sectors, followed by 20% in construction, 8% in IT and 4% in media.

“There is also some overlap between the construction and oil/gas/energy sectors. Some companies are involved in the construction of oil and gas plants, as well as other types of building projects,” says Ryan Robinson, a security researcher at Intezer.

“We cannot confirm any link to a previous campaign or threat actor at this point,” Robinson adds, noting that the use of command-and-control servers across the world makes it difficult to trace these attacks back to specific individuals or groups.

“It is also hard to determine the number of groups or people involved in this operation,” he says. “But from the volume of the emails sent and the amount of research put into crafting the lure documents in multiple languages, it would be unlikely that it is one singular person.”

Focus of Attack

Organizations that provide critical infrastructure are valuable targets for hackers because attacking them can cause mass disruption and accompanying ransom demands can reach millions of dollars, says Theresa Lanowitz, director of AT&T Cybersecurity.

Management consultancy firm McKinsey states that the utilities sector faces security challenges that are not found in other industries, making the situation even more challenging.

Whether it’s commercially minded cybercriminals seeking huge ransoms or nation-state-backed threat actors with different motives, the outcomes are the same – a great deal of damaging disruption, says Ed Stirzaker, cybersecurity firm Forcepoint’s head of local government and strategic accounts for the U.K. and Ireland.

In addition, systems inside organizations that are part of any critical infrastructure sector – as with any organization that makes use of IT – can often have a long and complicated software supply chain, with a mix of legacy systems and modern technologies spliced together. “It’s this complex network that targeted attacks can take advantage of,” Stirzaker says (see: Colonial Pipeline Restarts Operations Following Attack).

Attack Method

In the campaign spotted by Intezer, attackers impersonate an organization in the relevant industry and send employees of the victim organization phishing emails. The emails, which contain a business partnership proposal or a work opportunity, have an attachment – usually an IMG, ISO or CAB file. These file formats are commonly used by attackers to evade detection by email-based antivirus scanners, the report says.

The emails use social-engineering tactics such as making reference to executives and using physical addresses, logos and emails of legitimate companies. They also include requests for quotations, contracts and referrals/tenders for real projects related to the business of the targeted company.

In most of these emails, the file name and icon of the attachment mimic a PDF. The purpose is to make the file look less suspicious, enticing the targeted individual to open and read it, Intezer researchers say.

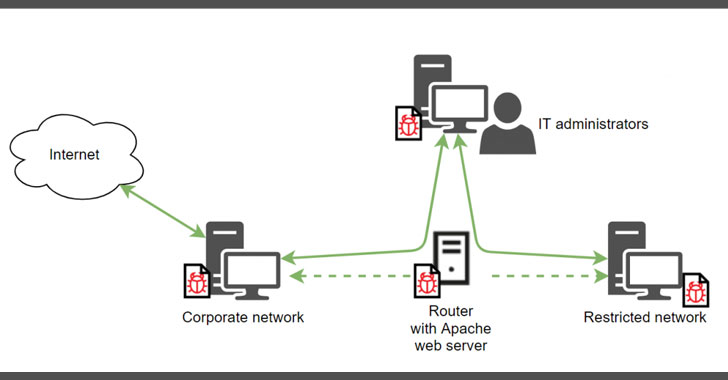

Once the victim opens the attachment and clicks on the contained files, an information stealer is executed.

Mimicking Legitimate Domain Names

In several emails, the attackers have registered a domain name that mimics a legitimate domain to increase the credibility of the spear-phishing attempt, the report says. This “typosquatting” fools email recipients into believing that an email has been sent from a trusted entity.

In this campaign, many of the counterfeit domains mimic South Korean companies with legitimate domains in the format of “company[.]co[.]kr,” the report says. An example is the domain “hec-co[.]kr,” registered by the attackers to typosquat the legitimate domain for the company Hyundai Engineering, which is “hec[.]co[.]kr.” The fake email from “Hyundai Engineering” invites the recipient to reply to a confidentiality agreement concerning a refinery expansion project.

Another victim of the campaign, Netherlands-based offshore equipment and technology services provider GustoMSC, posted an alert, warning users that the company’s domain had been hit by typosquatting and that scammers were sending emails on behalf of its employees.

Email Spoofing

Many email addresses in this campaign have been spoofed by the attacker, meaning the emails are sent with forged headers to make it appear as if they came from a trustworthy or reputable source, tricking users into opening the email attachments, Intezer reports.

One of the spoofed organizations is FEBC, a South Korean Christian radio station that broadcasts outside the nation, especially to countries that discourage or outlaw religion. One of FEBC’s goals is to overcome North Korea’s religious ban.