Ransomware Actors Set Up a Call Center to Lure Victims

Fraud Management & Cybercrime

,

Fraud Risk Management

,

Next-Generation Technologies & Secure Development

Microsoft Warns of Clever Social Engineering Using ‘BazaCall’ Malware

Ransomware actors have taken a page from the playbooks of tech support scammers of yore by guiding victims to download malware using persuasion over the phone.

See Also: Live Webinar | Improve Cloud Threat Detection and Response using the MITRE ATT&CK Framework

The technique was first spotted in February, according to Palo Alto Networks’ Unit 41 research unit. But Microsoft is issuing a fresh warning about the campaigns, contending they’re much more dangerous than it first realized. Microsoft calls the campaign “BazaCall.”

“In our observation, attacks emanating from the BazaCall threat could move quickly within a network, conduct extensive data exfiltration and credential theft, and distribute ransomware within 48 hours of the initial compromise,” write Justin Carroll and Emily Hacker of Microsoft’s 365 Defender Threat Intelligence Team.

The end result may be an infection with Ryuk or Conti – ransomware believed to be pushed by a Russia-based group known as Wizard Spider and its affiliates. The DFIR Report, which publishes deep technical dives into attacks, on Sunday published a detailed rundown of a BazaCall attack that led to Trickbot malware being installed, and, eventually, Conti.

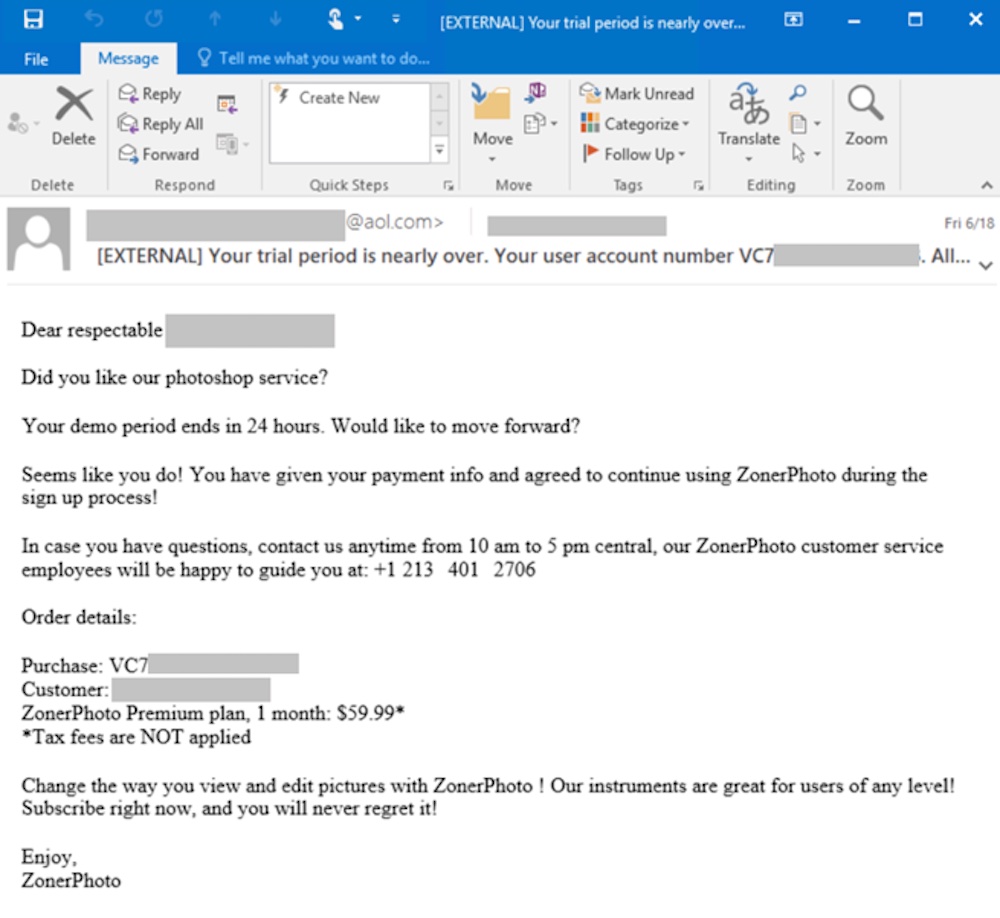

Clean Emails

BazaCall campaigns kick off with a targeted spam email as a lure. The email may warn that an expensive subscription, such as one for a photo editing service or a recipe website, may be automatically renewed. More recent BazaCall emails purport to be confirmation receipts for a purchased software license, Carroll and Hacker write.

The emails, however, contain no links or malicious attachments, which are triggers that send a message off to quarantine. The emails come from a different sender each time and are sent through free email services. The emails often purport to come from companies that are similar in name to those of real businesses in case people run a quick search.

The messages “instruct users to call a phone number in case they have questions or concerns,” Carroll and Hacker write. “This lack of typical malicious elements – links or attachments – adds a level of difficulty in detecting and hunting for these emails.”

An audio recording of a call to one of the BazaCall numbers was published on March 30 by Malware Traffic Analysis. The call center employee guides the victim to a website where they are directed to enter a subscription number.

Carroll and Hacker write that the subscription number or other numbers serve as identifiers to those executing and tracking the campaign.

The call center employee then guides the victim to a website that looks like a legitimate business. The victim is then instructed to download a file, such as an Excel spreadsheet.

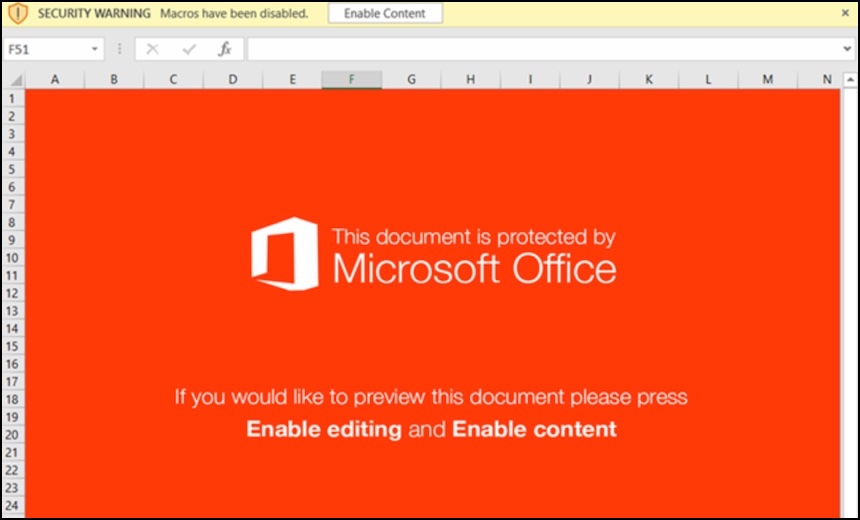

In the audio call, the user is guided to enable macros after a warning is displayed. Eventually, the victim is told that their subscription has been successfully canceled, but instead, the BazaLoader malware has been installed.

Data Exfil, Possibly Ransomware

The infected computer is then ready for the next stage of the attack.

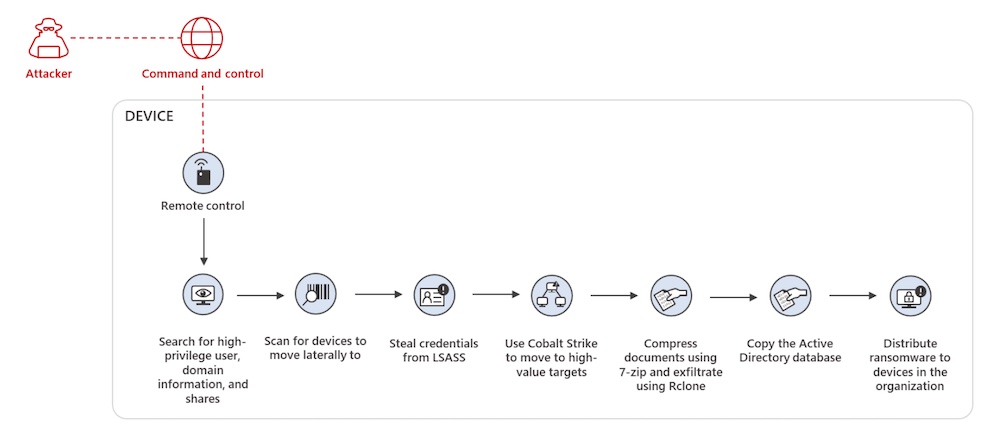

The macro creates a new folder and copies certutil.exe, a legitimate tool, in that folder. Certutil.exe then connects to BazaLoader’s infrastructure. Eventually, the malware retrieves a Cobalt Strike beacon. Cobalt Strike is a penetration testing toolkit, and its beacon is a tool for delivering payloads, issuing commands and performing tasks on a target’s network.

“Now with direct access, the attacker performs reconnaissance on the network and searches for local administrators and high-privilege domain administrator account information,” Carroll and Hacker write.

The attackers may then hunt around for Active Directory and then use AdFind, a tool for querying Active Directory. They may also try to pull a copy of the NTDS.dit Active Directory database, which includes user information and password hashes for all users in the domain.

“Once the attacker has established a list of target devices on the network, they use Cobalt Strike’s custom, built-in PsExec functionality to move laterally to the targets,” Carroll and Hacker write. “Each device the attacker lands on establishes a connection to the Cobalt Strike C2 server.”

In some cases, it appears the attackers are just interested in exfiltrating data. But in others, it’s ransomware time. The time span between the initial compromise and when ransomware is deployed may be as little as 48 hours, Carroll and Hacker write.

“In those cases where ransomware was dropped, the attacker used high-privilege compromised accounts in conjunction with Cobalt Strike’s PsExec functionality to drop a Ryuk or Conti ransomware payload onto network devices,” Carroll and Hacker write.