NIST Drafts Elections Security Guidance

Cyberwarfare / Nation-State Attacks

,

Endpoint Security

,

Fraud Management & Cybercrime

Agency Describes How to Apply Its Cybersecurity Framework

The National Institute of Standards and Technology has drafted guidelines for how to use its cybersecurity framework to address cyberthreats and other security issues that can target state and local election infrastructure and disrupt voting.

See Also: Live Webinar | Mitigating the Risks Associated with Remote Work

A draft of guidelines – Cybersecurity Framework Election Infrastructure Profile or NISTIR 8310 – released Monday addresses election-related issues ranging from the protection of polling places to cyberthreats that can affect voter registration databases, voting machines and the networks that connect them.

The guidelines are designed to give state and local officials a way to reduce election risks, including before and after the vote, while offering standards to ensure data and networks are protected against attacks and intrusions.

NIST is accepting comments on the election security draft document until May 14 and will release final guidance once it reviews the comments.

Applying the Cybersecurity Framework

NIST says the draft shows how to apply the principles of its Cybersecurity Framework to the nation’s election infrastructure at the state and local level. The agency published the most recent version of the framework in 2018 (see: Highlights of NIST Cybersecurity Framework Version 1.1).

“There are several thousand voting jurisdictions in the United States,” NIST notes. “While state and federal governments play roles in elections, such as providing training courses on running the state’s elections and providing a process for testing and certifying voting equipment, most of the nitty-gritty work of running an election happens at the city or county level, with individual polling places staffed largely by volunteers.”

NIST designed the guidance for use by election officials, voting device manufacturers and developers of voting systems.

Frank Downs, a former NSA offensive threat analyst who is now director of proactive services at the security firm BlueVoyant, notes that by creating these election security guidelines, NIST can help reduce the hodgepodge approach to election security that has hampered voting in the past – citing, for example, the trouble with the mobile app that malfunctioned during the Democratic Party’s Iowa caucus in February 2020 (see: Report: Iowa Caucus App Vulnerable to Hacking).

“The framework will provide these organizations with a mechanism to identify key controls, which apply to their election, and point to guidance on how best to implement those controls,” Downs says. “In doing this, these election organizations will be able to better secure their elections in a methodical, organized and scalable fashion – no matter the size or location of the election.”

Election Interference

Earlier this month, U.S. intelligence agencies released several reports that found nation-states such as Russia, China and Iran tried to interfere in the 2020 election by running disinformation campaigns. But the studies found no attempt by foreign hackers to directly manipulate vote tabulations or results (see: US Intelligence Reports: Russia, Iran Targeted 2020 Election).

The reports did find, however, that hackers from Russia, China and Iran cracked the security of networks associated with campaigns and candidates and accessed some data. They offered a series of election security recommendations, including using firewalls to protect voter data and improving security around supply chains.

In 2017, the Department of Homeland Security designated the country’s election system as part of America’s critical infrastructure, NIST notes, and voting equipment and information systems that support elections should be protected from cyberthreats.

The guidelines are meant “to engender risk-based cybersecurity decisions for a certain subset of election infrastructure using specific mission objectives identified by the community,” according to the draft document. State and local election officials should also continue to follow directives and recommendations made by DHS and the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, NIST advises.

Security Recommendations

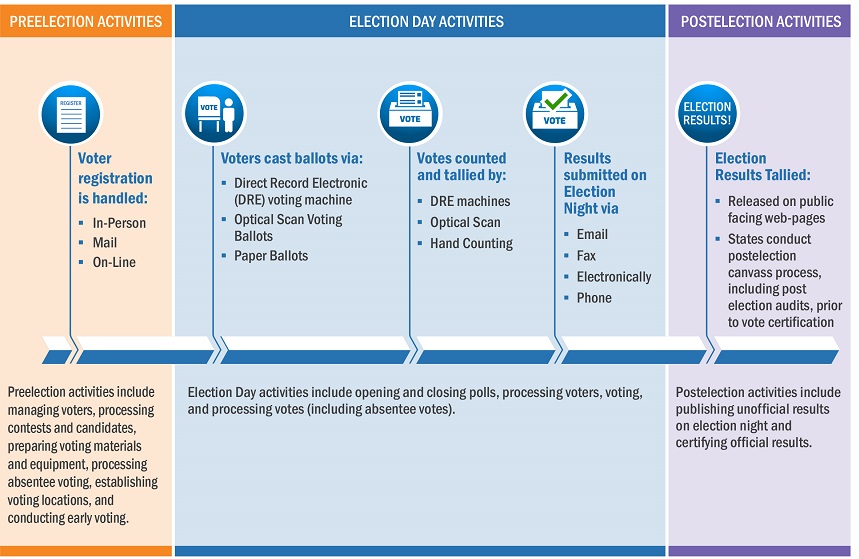

The draft guidelines break down U.S. elections into three areas of risk:

- Pre-election activities, such as managing voters, processing candidates and contests, preparing voting materials and preparing voting machines and processing early voting.

- Election day activities, which include the opening and closing of polling places, the security of the machines and the collection of absentee ballots.

- Post-election duties, such as publishing unofficial accounts and preparing to certify the election.

NIST says the draft guidelines are designed to address various security and threat scenarios that could occur during these three stages. And organizations can pick and choose which parts of the guidelines they want to follow.

“Election infrastructure may come under cyberattack or be subject to natural disasters, and the appropriate defenses and contingencies should be identified and tailored to the subsector’s needs,” according to NIST.

The election guidelines outline what NIST calls “five continuous functions” that can help provide a strategic overview of an organization’s cybersecurity posture. These are: identify, protect, detect, respond and recover.

The draft guidelines, for example, describe how to apply these functions to what NIST calls “conducting and overseeing voting period activities.”

In a section on “maintaining a workforce,” the guidelines show how to apply these functions to helping poll workers protect personal data that is entrusted to them and helping election officials reduce insider threats.

“The guide can help these officials reduce the risk of disruptions to the major tasks they must perform in the process of an election,” NIST states. “These range from the immediate concerns of an election day, such as vote processing or communicating the details of a problem or crisis, to longer-term efforts, like maintaining election and voter registration systems.”