Law Enforcement’s Cybercrime Honeypot Maneuvers Paying Off

Cybercrime

,

Cybercrime as-a-service

,

Endpoint Security

Closing EncroChat and Sky, Plus Careful Word-of-Mouth Management, Drove Anom Uptake

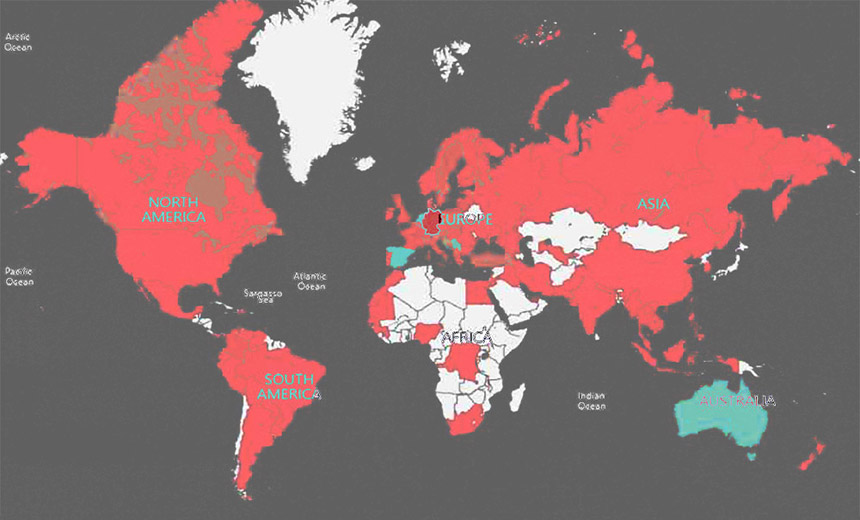

The global law enforcement “Anom” honeypot operation racked up impressive statistics for the number of criminals tricked into using the encrypted communications service run by the FBI.

See Also: Live Webinar | The Role of Passwords in the Hybrid Workforce

“Thousands of criminal users wrongly believed themselves to be unobserved in their communication via this service,” said Jannine van den Berg, chief commissioner of the Netherlands’ National Police Unit, at a June 8 press conference. “Eventually, hundreds of criminal organizations were using this platform. It has a good reputation among criminals. They mutually promoted it as the platform you should use for its absolute reliability. But nothing was further from the truth.”

“Cybercrime finds a way. Other criminals and services rise from the ashes.”

The operation, also led by Australia, the Netherlands, New Zealand and Sweden, and backed by the EU’s law enforcement agency, Europol, and the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency, also delivered another important type of disruption: sowing long-term mistrust and doubt.

Anom was the latest in a long line of services supposedly built by criminals, for criminals, that were in turn used by authorities against criminals.

Many Criminals Avoid WhatsApp, Signal

For whatever reason, criminals appear to mistrust mainstream encrypted communications services, perhaps fearing that they have been backdoored or otherwise coopted by law enforcement or intelligence agencies.

“It’s notable that the criminals would rather trust an app that their ‘friends’ recommended than WhatsApp or Signal that seem to have worried governments so much,” Alan Woodward, a visiting professor at the University of Surrey, told me when the Anom sting became public last week. “It’s as if the criminals think that mainstream app messengers have already been compromised by governments.”

Instead, for encrypted communications, in recent years many criminals have relied on services that provide subscribers with a customized handset, which allows them to only send and receive text messages and images and has all nonessential functionality – microphone, GPS, headphone socket, USB port – stripped out so the devices can’t be used to surreptitiously survey or track users.

But service after service has been targeted by law enforcement agencies and taken down, from Phantom Secure in 2018, to EncroChat in June 2020, to Sky ECC – aka Sky Global – in March. In each of those cases, the service administrators also were charged with crimes tied to facilitating the criminal use of their services. Some are now serving federal sentences.

For both EncroChat and Sky, law enforcement agencies were able to surreptitiously gain access to the networks, monitor communications, and gather and share intelligence with global partners. Intelligence from those efforts continues to result in arrests, recently including suspects in France and the Netherlands.

In the case of Anom, since the FBI and Australian Federal Police launched it in 2018 with a handful of users during a beta trial in Australia, before growing to 9,000 active users globally, law enforcement agencies said they were lately having a difficult time keeping up with the quantity of intelligence being generated – although from a policing standpoint, that doesn’t sound like the worst problem in the world. According to court documents, the operation came to an end because judicial approval in one of the participating countries was set to expire.

Law enforcement officials last week noted that the takedown of encrypted messaging services has historically driven users to switch to another offering – and often the next largest. After the EncroChat and Sky Global takedowns, for example, they said Anom’s user base dramatically increased.

Serial Darknet Market Takedowns

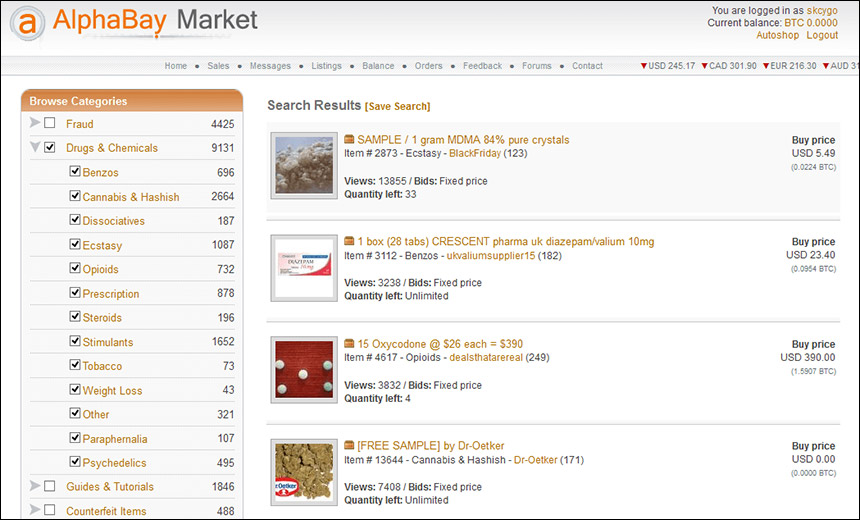

Law enforcement agencies have applied similar tactics before in other digitally enabled crime realms, such as darknet markets.

One of the best-known examples involved the darknet marketplace AlphaBay, launched in December 2014, which was run by Canadian Alexandre Cazes from Thailand. Authorities say he amassed about $23 million, thanks to his site charging a commission of 2% to 4% on every transaction.

On July 4, 2017, AlphaBay went dark, which drove many users to seek alternatives, including the popular Hansa marketplace. But unbeknownst to Hansa users, it had been taken over by Dutch police the month before, and they monitored everything being done on Hansa for one month, before shutting it down on July 20, 2017. The same day, authorities revealed the operation and Cazes’ arrest.

“Dutch police collected valuable information on high-value targets and delivery addresses for a large number of orders,” Europol said at the time, noting that it had received “some 10,000 foreign addresses of Hansa market buyers” that it shared with authorities in those countries.

Cazes, meanwhile, had lived large for nearly three years before being arrested. Facing extradition to the U.S., he was found dead in his Bangkok jail cell, having apparently taken his own life.

Darknet Markets Carry On

In the case of the quiet infiltration of Hansa and takedown of AlphaBay, driving users to Hansa, law enforcement agencies turned darknet market users’ proclivity for simply moving to another service when a current one becomes unavailable against them.

But despite such sting operations, just like encrypted messaging services, darknet markets continue to operate.

Ease of use – and a lack of good alternatives – help explain why darknet markets persist, even as users face the risk that they’re being watched by police. Many markets also offer ratings of sellers and goods and escrow services that protect buyers and sellers in case of nonpayment or nonfulfillment.

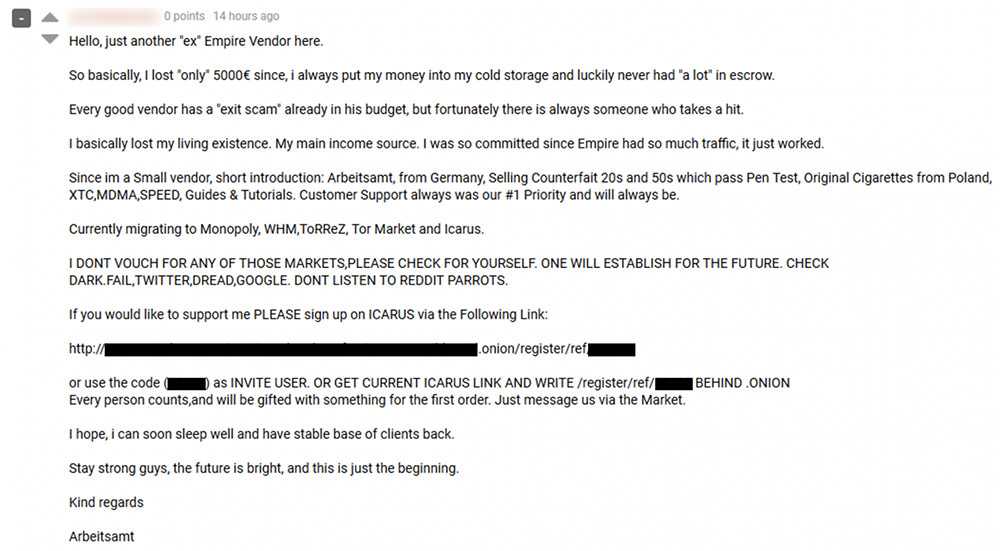

But that creates another risk: Sometimes, administrators decide to take all the cryptocurrency they’re holding in escrow and “exit scam,” making themselves millions of dollars richer.

Beyond darknet markets, some sellers of illegal goods and services on the internet appear to rely on encrypted chat apps, such as Telegram, WhatsApp, Discord, Jabber and Wickr. But experts say that while such apps can encrypt communications, buyers and sellers still need a way to find each other, which drives many back to darknet markets.

Perhaps the serial disruptions and takedowns of darknet markets and encrypted communications services have led some individuals to reconsider their decision to pursue crime or buy or sell illegal goods. Certainly, in the wake of some takedowns and disruptions, some markets outlawed narcotics, hoping to lower the chance that they might get targeted by police.

New Services Fill Gaps

But fresh sites inevitably seem to emerge to fill gaps in the cybercrime market. “As is always the case after law enforcement actions, cybercrime finds a way,” says Rick Holland, CISO at cybersecurity firm Digital Shadows. “Other criminals and services rise from the ashes.”

From a disruption standpoint, however, the law enforcement tactic of penetrating services used by criminals and collecting intelligence doesn’t just serve as a psychological strategy, by helping sow doubt and mistrust over the reliability or integrity of any such service. It also helps investigators identify and directly target suppliers and users, including users of malware, money laundering, cashout and other cybercrime tools and services.

“Cutting the head off the snake gives some respite,” the University of Surrey’s Woodward says. “But catching those who would use such a service helps suppress the ‘market’ and hence there is less reason for someone to start a replacement.”