Is Cryptocurrency-Mining Malware Due for a Comeback?

Blockchain & Cryptocurrency

,

Critical Infrastructure Security

,

Cryptocurrency Fraud

If Ransomware Should Decline as a Viable Criminal Business Model, What Comes Next?

The world is now focused on ransomware, perhaps more so than any previous cybersecurity threat in history. But if the viability of ransomware as a criminal business model should decline, expect attackers to quickly embrace something else – but what?

See Also: Live Panel | Zero Trusts Given- Harnessing the Value of the Strategy

We’ve been here before. In late 2017, driven by a surge in bitcoin’s value, many criminals shifted from using ransomware, which at the time was typically spread via drive-by downloads and spam attacks, to using the same tactics to instead spread cryptocurrency-mining malware.

“Cryptomining is designed to evade detection and stay active for long periods of time, and the targeting makes little to no difference other than the amount of currency they can generate.”

Attackers don’t seem to prioritize any given approach over another. Or at least if there was a cult devoted to the first type of ransomware ever seen in the wild – the AIDS Trojan, which in 1989 began spreading via floppy disk – any lingering adherents would be in dire need of a day job.

For criminals, different types of malware – banking Trojans, ransomware, spyware, rootkits – are simply tools. So too are business email compromise scams, phishing and other types of online-enabled crime.

The bottom line for professional cybercriminals: Time is money. So, expect them to pursue the quickest route to maximum profits with minimal risk and effort. Also expect others to follow when they see that something is successful.

Ransomware’s Success Story

Lately, ransomware has been delivering in spades, thanks to continuing business refinements. By pursuing larger targets via big game hunting, some criminals have realized much higher ransom payoffs with little additional effort. The rise of service-based models, meanwhile, has given attackers – of all skill levels – access to high-quality crypto-locking malware with which to infect victims. When a victim pays, the affiliate and operator share the payoff, and profits from this type of illicit business model have been booming.

Now the Biden administration and allies have been moving to attempt to disrupt the ransomware business model via law enforcement means and cracking down on cryptocurrency flows, neither of which so far have been hugely successful. But President Biden is also trying to make it more costly for leaders of countries – such as Russia, where many of these criminals reside – to tolerate or encourage such attacks. Western allies might even attempt to disrupt criminals’ infrastructure via offensive hacking operations.

Whether such strategies will work remains to be seen. And no changes will happen overnight.

What Comes Next?

If these disruption strategies bear fruit, what will happen next? In other words, where will criminals turn to maximum their cybercrime profits?

If ransomware gets disrupted, it’s a sure bet that more attackers will turn to cryptomining malware, even though how each gets wielded typically differs. “Both provide financial gain in completely different ways,” says Nick Biasini, a threat researcher at Cisco Talos, in a blog post. “Ransomware targets enterprises specifically, is noisy and requires actors to establish and maintain communication avenues with their victims. Cryptomining is designed to evade detection and stay active for long periods of time, and the targeting makes little to no difference other than the amount of currency they can generate.”

Cryptocurrency mining refers to solving computationally intensive mathematical tasks. In the case of bitcoin, such tasks are used to verify the blockchain, or public ledger, of transactions. As an incentive, anyone who mines for cryptocurrency has a chance of getting some cryptocurrency back as a reward. But for bitcoin and some other types of cryptocurrency, the amount of reward decreases as more blocks get added.

Mining can consume copious amounts of electricity – so much so, that some studies have found it would be cheaper to buy gold outright rather than obtain cryptocurrency via mining. Such calculations are always in flux, with the rise and fall in cryptocurrency value. But for attackers, the easiest approach is to have someone else pay for the power while they walk away with the cryptocurrency.

Illicit Monero Mining Tracks Value

While ransomware attacks have skyrocketed again in recent years, the quantity of cryptocurrency mining malware being detected in the wild hasn’t fallen off sharply, but rather has steadily increased, especially with surges in cryptocurrency value.

So says Biasini, based on his analysis of monero. “Monero is a favorite for illicit mining for a variety of reasons, but two key points are: It’s designed to run on standard, nonspecialized hardware, making it a prime candidate for installation on unsuspecting systems of users around the world, and it’s privacy-focused,” which has led some ransomware operations, such as REvil – aka Sodinokibi – to prefer it.

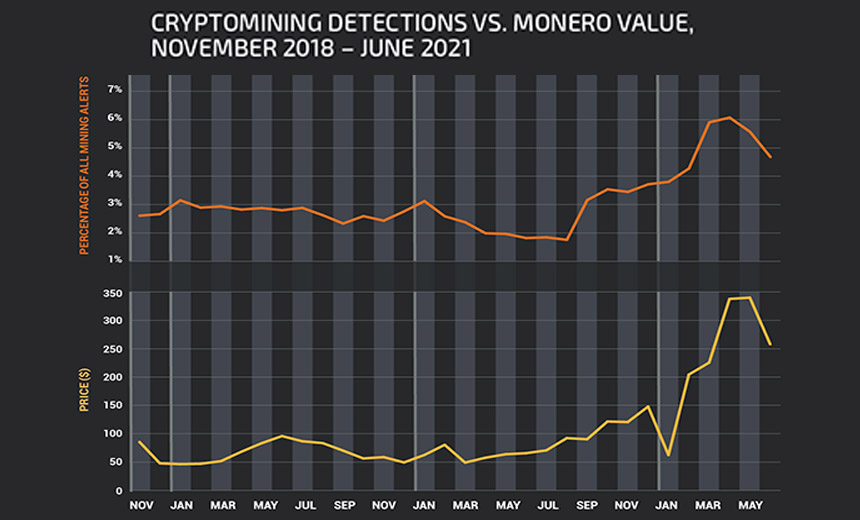

Comparing the value of monero with in-the-wild detections of malware designed to mine for monero, Biasini found that aside from a brief drop in monero’s price earlier this year, the graphs for each appear to track closely together.

“This was honestly a pretty surprising correlation, since it’s believed that malicious actors need a significant amount of time to set up their mining operations, so it’s unlikely they could flip a switch overnight and start mining as soon as values rise,” he says. “This may still be true for some portion of the threat actors deploying miners, but based on the actual data, there are many others chasing the money.”

Takeaways for CISOs

Biasini’s research shows that cryptocurrency-mining malware attacks are already a significant threat – and of course may become even more of a threat if criminals move away from ransomware.

The takeaway for security teams, as ever, is vigilance, because if attackers can sneak cryptominers onto an organization’s systems – eating up processing power and racking up sky-high electricity bills – they might put something nastier there too. “Unauthorized software on end systems is never a good sign,” Biasini says. “Today, it’s a cryptominer; tomorrow, it could be the initial payload in an eventual ransomware attack.”

That’s why he advocates treating cryptominers as a serious security threat. “Leaders need to understand that any drastic changes in these dynamics will shift the threat landscape,” he says. “If, say, governments decide to start cracking down on ransomware cartels or work more aggressively against cryptocurrencies, the threat landscape is going to react. Based on the mining data we saw here, the shift might occur relatively quickly.”