REvil’s Ransomware Success Formula: Constant Innovation

Cybercrime

,

Cybercrime as-a-service

,

Fraud Management & Cybercrime

Affiliate-Driven Approach and Regular Malware Refinements Are Key, Experts Say

Just as cloud services have taken the business world by storm, the same can be said for ransomware, including one of today’s most notorious strains: REvil. Also known as Sodinokibi and Sodin, REvil is a ransomware-as-a-service offering, which means a core group develops and maintains the ransomware code and makes it available to affiliates via a portal.

See Also: Live Panel | Zero Trusts Given- Harnessing the Value of the Strategy

Those affiliates and the core group of operators share in any profits that result from victims paying a ransom. Recent victims that have made payments include meat processor JBS, which paid $11 million in bitcoins.

Many security experts rank REvil among the most damaging and prevalent RaaS operations, alongside Conti, DoppelPaymer (aka DopplePaymer), Maze offshoot Egregor, and Ryuk.

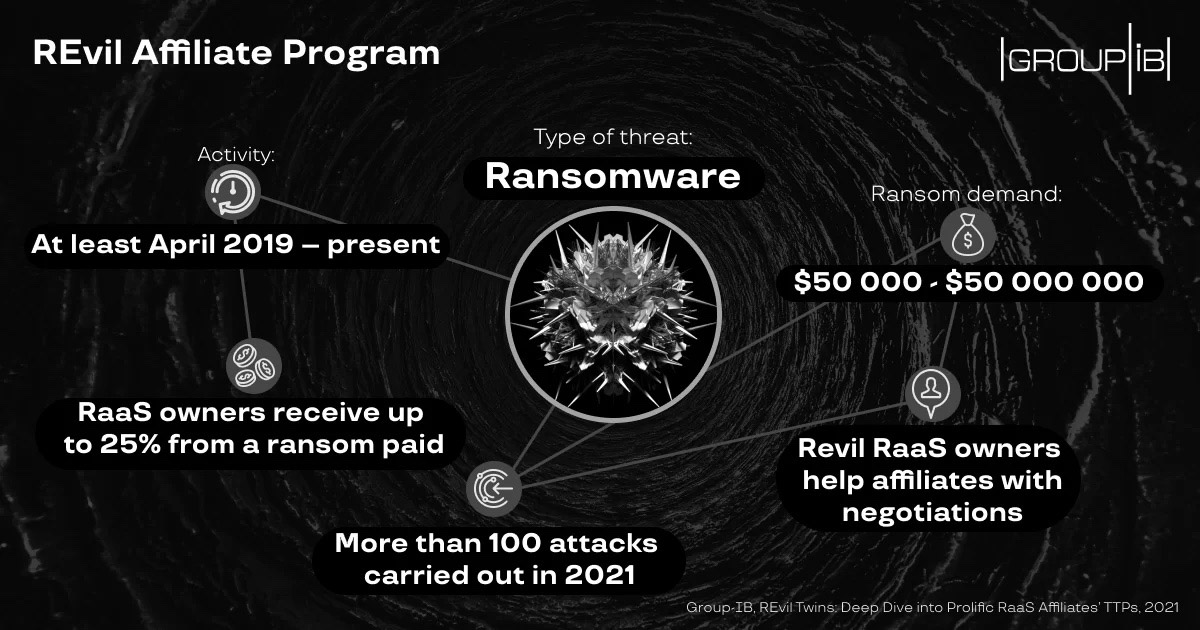

A key to REvil’s success has been its use of skilled affiliates and their ability to successfully access and traverse increasingly large victims’ networks, infect endpoints – now including both Windows and Linux systems – and demand larger ransoms. REvil’s operators also maintain a data leak portal and can assist affiliates with ransomware negotiations. All of this has one goal: to get victims to pay.

Affiliate Operations

Like other RaaS operations, REvil affiliates use a portal to generate fresh crypto-locking malware executables, with each designed to be just different enough from the others to make it difficult for security defenses to detect it.

After affiliates procure a new build of the malware, they use it to infect a victim and leave their files encrypted, except for a ransom note that demands anywhere from $50,000 to $50 million, according to cybersecurity firm Group-IB.

In 2019, every time a victim paid a ransom, the operator’s cut was 40%, dropping to 30% after an affiliate notched up three successful ransom payments. More recently, Group-IB says, the operator’s cut may have fallen to 25%. The firm also notes that as with some other RaaS operations, REvil’s core operators often handle negotiations with victims.

Experts say this relatively specialized approach – an operator maintaining code and supporting services, and an affiliate infecting victims – has helped drive ongoing increases in the number of organizations being hit as well as the amount of ransom they’re paying. And REvil stands as one of the most successful such operations in recent years.

The Rise of REvil

REvil first appeared in April 2019, seemingly as a spinoff or offshoot of the GandCrab RaaS operation, which “retired” the following month.

The REvil operation quickly began racking up impressive profits, aided by relatively specialized affiliates wielding advanced network penetration skills, and targeting not just poorly secured remote desktop protocol connections but also exploiting unpatched remote-access software from Citrix and Pulse Secure.

Today, the REvil operation remains prolific, with recent big-name victims including JBS, computer maker Acer – REvil demanded a $50 million ransom – as well as University Medical Center of Southern Nevada and Apple equipment manufacturer Quanta, among many others.

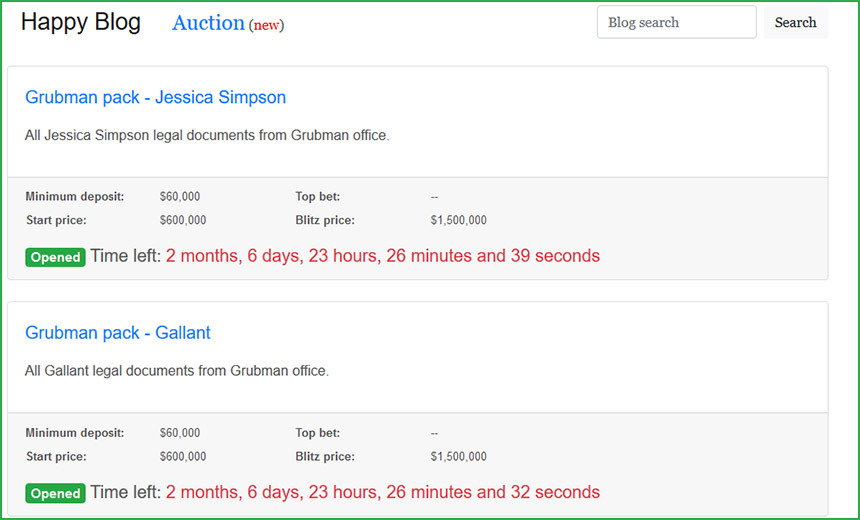

On Thursday, REvil’s “Happy Blog,” where affiliates can name victims and post extracts of stolen data, listed four new victims: a U.S. manufacturer, a Spanish telecommunications firm and a healthcare firm and construction firm, both in Brazil.

Distribution Tactics

How ransomware gets distributed continues to evolve, and REvil is no exception.

Targeting poorly secured RDP remains a common attack vector, as do phishing attacks. Recently, for example, “REvil affiliates have been seen using a spam campaign to deliver malicious documents and exploit kits targeting old vulnerabilities on unpatched machines as well as most recently through Qakbot,” Chad Anderson, a senior security researcher at cyberthreat intelligence firm DomainTools, writes in a new research report.

Group-IB reports that in addition to using the Qakbot botnet – previously used by ProLock, Egregor and DoppelPaymer – REvil affiliates have also been using the IcedID botnet, which has been previously used by affiliates of Maze, Egregor and Conti. Of course, these affiliates may now be working also with REvil; some experts say such relationships are rarely exclusive.

For REvil affiliates using Qakbot or IcedID, “both Trojans are distributed via massive spam campaigns,” Group-IB says. “A potential victim receives an email with a weaponized Microsoft Office document, and if it’s opened and malicious macros are enabled, the Trojan binary is downloaded and executed on the host.”

The move by REvil affiliates to use botnets makes sense financially: Time is money. “With the speed at which many of these ransomware groups are now moving and the money involved, purchasing access from botnet operators into valuable victim networks is more effective than individual targeting of companies for most affiliates,” Anderson says.

Target Selection

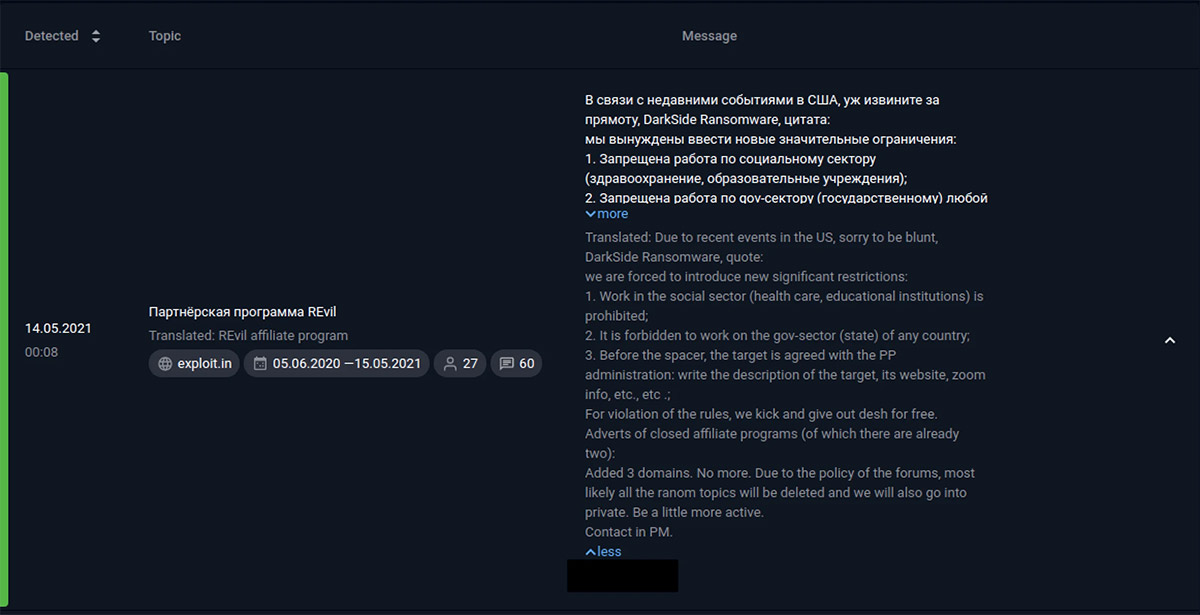

Following the DarkSide operation’s hit on Colonial Pipeline Co. in the U.S. in May, REvil and other gangs began prohibiting affiliates from hitting certain types of targets and also said they would require permission before deploying the malware against any organization. Experts say it’s not clear whether those are hard-and-fast rules or were simply issued as face-saving missives in light of growing geopolitical pressure on Moscow to crack down on ransomware operations based inside Russia.

When it comes to hitting targets, different REvil affiliates have different skill sets and strategies. “REvil affiliates didn’t always focus on big game hunting,” Oleg Skulkin, a senior digital forensics analyst at Group-IB, writes in a new report.

He notes that last December, for example, at least some REvil affiliates were aiming for “companies with relatively small revenues” by using malvertising – injecting malicious code into legitimate advertising networks – “to trick victims into downloading an archive with a malicious JavaScript file.” If executed, the file “abuses Windows Command Prompt to run a malicious PowerShell command, which finally leads to REvil execution on the target host,” he says.

Post-Exploitation Tools

Regardless of the target size, some affiliates may bring more advanced hacking skills to bear. After gaining access to a victim’s network, for example, Group-IB says post-exploitation tools used by REvil affiliates often include Cobalt Strike, Metasploit, CrackMapExec, PowerShell Empire and Impacket.

“Usually, the threat actors use post-exploitation tools in a quite common way, so if you focus on regular command line arguments typical of Cobalt Strike, PowerShell Empire and others, you’ll most likely successfully detect them,” Skulkin says.

For example, security firm Sophos on Wednesday described a REvil attack in early June against a “mid-size media company” that it helped investigate, which came to light – and was disrupted – precisely because the organization detected the use of Cobalt Strike inside its network.

Technical Teardown: REvil Malware

Security experts say that like most types of ransomware, before crypto-locking a system, REvil first ensures that the system language isn’t set to any country inside the Commonwealth of Independent States, which includes Russia and Ukraine. If so, the malware will shut down (see: Russia’s Cybercrime Rule Reminder: Never Hack Russians).

If the malware proceeds, DomainTools’ Anderson says, it uses multiple tactics to improve its chance of success. “For instance, REvil samples will attempt to escalate privileges by constantly spamming the user with an administrator login prompt or will reboot into Windows Safe Mode to encrypt files, as antivirus software rarely runs in safe mode,” he says. “REvil uses the AES or Salsa20 encryption algorithms on victim files, which is a slightly unique signature.” REvil’s operators also appear to have implemented the encryption in a manner that cannot be brute-force cracked to decrypt files.

REvil Debuts Linux Ransomware

Ransomware operators attract affiliates via their profit-sharing incentives as well as the quality of their malware. Evading detection is key. For affiliates pursuing big game hunting, a critical factor is the ability to encrypt and restore files – if a victim pays a ransom – without accidentally shredding them.

Recently, REvil also ported its Windows malware to Linux to target network-attached storage devices as well as systems running the VMware ESXi hypervisor, Fernando Martinez and Ofer Caspi, security researchers at AT&T Cybersecurity’s Alien Labs, write in a Thursday blog post.

REvil’s Linux move was first reported in early May by threat intelligence firm Advanced Intelligence, and such code began to be seen in the wild later that month.

“These software upgrades follow the trend seen in other popular RaaS groups, like DarkSide, where they have added Linux capabilities to include ESXi in their scope of potential targets,” Martinez and Caspi write. Babuk ransomware, for example, also offers similar Linux-infecting capabilities.

Targeting ESXi gives attackers a way to hit a hard drive that may be running multiple virtual machines. “The hypervisor ESXi allows multiple virtual machines to share the same hard drive storage,” Martinez and Caspi write. “However, this also enables attackers to encrypt the centralized virtual hard drives used to store data from across VMs, potentially causing disruptions to companies.”

REvil Operations Keep Evolving

As the Linux variant of REvil demonstrates, successful ransomware operations constantly evolve.

For example, researchers at security firm Secureworks last week reported that a supposedly new strain of ransomware, called LV, is really a repurposed version of REvil. Whether the code was shared by REvil, or stolen by LV’s operators, isn’t clear.

REvil’s success has led others – such as newcomer Prometheus – to directly claim that they’re part of the operation. Whether or not this is true, the goal is simple: “to encourage victim payment,” DomainTools’ Anderson says.

“All of these groups make alliances, share tools and sell access to one another,” Anderson says. “Nothing in this space is static, and even though there is a single piece of software behind a set of intrusions, there are likely several different operators using that same piece of ransomware that will tweak its operation to their designs.”

Thus the business of ransomware continues, ever in pursuit of fresh illicit profits.