Babuk Ransomware Mystery Challenge: Who Leaked Builder?

Critical Infrastructure Security

,

Cybercrime

,

Cybercrime as-a-service

Code for Generating Unique Copies of Crypto-Locking Malware Uploaded to VirusTotal

The code used to build copies of Babuk ransomware – to infect victims with the crypto-locking malware – has been leaked, after someone uploaded the software on Sunday to malware-scanning service VirusTotal.

See Also: Live Panel | Zero Trusts Given- Harnessing the Value of the Strategy

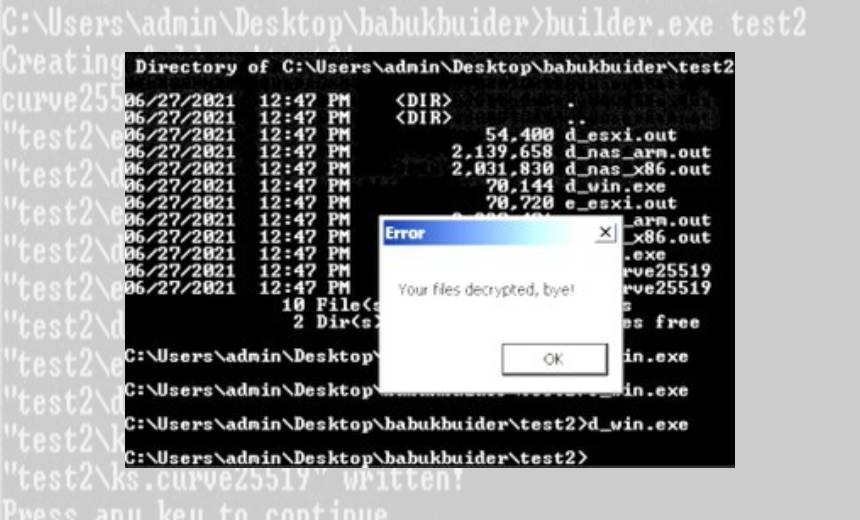

The VirusTotal upload, which was spotted by British security researcher Kevin Beaumont, contains a Windows executable file named “Babukbuilder,” which Beaumont says is “used by Babuk ransomware group for making Babuk payloads and decryptors.”

Whether the leak was accidental or intentional – perhaps a rival gang seeking to burn the operation – remains unclear.

Builders are used to generate malicious executables – aka payloads – that ransomware-wielding attackers deploy on victims’ systems. They can be used by a ransomware gang’s operators or third-party affiliates that work with the group, and will typically be designed to vary the executable file that gets generated each time, so that it doesn’t match any signatures for known malicious code.

Ransomware leak time – Babuk’s builder. Used for making Babuk payloads and decryption.

builder.exe foldername, e.g. builder.exe victim will spit out payloads for:

Windows, VMware ESXi, network attached storage x86 and ARM.

note.txt must contain ransom.https://t.co/K3J3zr1XBv pic.twitter.com/1bl7oc0TvO

— Kevin Beaumont (@GossiTheDog) June 27, 2021

How the code got uploaded to a malware-checking service remains unknown. Malware developers typically use other methods – obtained via the cybercrime-as-a-service ecosystem – for seeing if antivirus scanners will flag any given executable as being malicious. Still, perhaps the wrong file got uploaded by mistake by either Babuk or one of its partners or users. Or the upload may have been the work of a rival gang or unhappy business partner, seeking to burn the operation.

The Babuk builder, Beaumont says, generates code that will work on “Windows, VMware ESXi, network-attached storage x86 and ARM,” respectively referring to Microsoft’s operating system, as well as a widely used VMware hypervisor and NAS devices. Many organizations rely on NAS as part of their backup and restore strategy, meaning that if attackers can crypto-lock not just Windows PCs but also such backups, then more victims may be driven to pay a ransom for the promise that they’ll receive a decryption tool to restore data.

Previous Leaks

Cybersecurity vendor Recorded Future’s news site The Record says it obtained a copy of the builder from Beaumont and verified that it works as advertised. It also reports that the leak follows the source code for Paradise ransomware getting posted earlier this month to the Russian-language XSS cybercrime forum, although there’s nothing to suggest the two incidents are connected.

These aren’t the only times ransomware-building source code has been in circulation. Last year, for example, attacks were traced to a group of Persian-speaking hackers operating from Iran who appeared to be wielding Dharma ransomware for financially motivated attacks against targets in China, India, Japan and Russia. Dharma, also known as CrySis, first appeared in 2016, after which multiple variations were in circulation, with some becoming available for sale. Last year, notably, the source code for one such Dharma variant was being sold for $2,000 via a Russian cybercrime forum, apparently targeted at more entry-level, low-skilled attackers – aka script kiddies – according to security firm Sophos.

Babuk Rebrands as Payload.bin

What’s also unclear about the Babuk source code leak is if it might trace to an older version of the operation’s ransomware. Notably, Babuk recently rebranded as Payload.bin, aka PayloadBin.

Confusingly, the notorious Evil Corp crime gang then appeared to have rebranded its WastedLocker ransomware – aka PhoenixLocker and Hades – as PayloadBin, says Fabian Wosar, CTO of security firm Emsisoft. He said the “rebranding” still involved the WastedLocker executable and appeared to be “an attempt to trick victims into violating OFAC regulations,” referring to U.S. sanctions that prohibit anyone – including ransomware victims – from sending money to Evil Corp without prior approval of the U.S. Treasury Department.

Shift to a Ransomware-as-a-Service Model

Babuk’s rebranding followed the operation in April reporting that it would cease running its own attacks and instead proceed using a ransomware-as-a-service model.

Whether what any of these ransomware operations say is true remains unknown. Many of their claims turn out to be little more than self-promoting spin, if not outright lies (see: Ransomware Gangs ‘Playing Games’ With Victims and Public).

The RaaS approach that Babuk has claimed it will now practice involves the operator creating ransomware code and offering it to affiliates, who take the code and infect victims’ systems. Whenever a victim pays, the responsible affiliate keeps a majority of the profit, with the operator receiving the rest.

Affiliates often work with multiple RaaS operations, and some experts say many operations attempt to attract the best criminal hackers by offering more advanced attack code as well as accompanying services, such as data leak sites for pressuring victims into paying, as well as ransom-payment negotiation teams and better profit-sharing deals.

As the leak of Babuk’s source code demonstrates, however, well-laid business plans don’t always proceed as scheduled.

In fact, this is the second major setback to be recently experienced by the group. Its claimed shift to a RaaS approach, notably, appeared to be a duck-and-cover maneuver following the public and political outcry generated after the operation attempted to extort the police department in Washington, D.C. In fact, a number of high-profile attacks against U.S. targets in recent months have led to multiple ransomware operations vowing to restrict affiliates’ target lists or even retire altogether. The Avaddon operation, notably, announced it was closing and released all of the encryption keys victims would require to decrypt their systems (see: ‘Fear’ Likely Drove Avaddon’s Exit From Ransomware Fray). Whether or not that operation or its players return in rebranded form remains to be seen.